General persistence of physical activity habits despite decline in participation during adolescence

A recent Scientific Reports study elucidated the patterns of physical activity participation and discontinuation based on puberty timing during adolescence. Study: Puberty timing and relative age as predictors of physical activity discontinuation during adolescence. Image Credit: Pressmaster/Shutterstock.com Background

Study: Puberty timing and relative age as predictors of physical activity discontinuation during adolescence. Image Credit: Pressmaster/Shutterstock.com Background

The intensity of physical activity markedly declines in childhood and adolescence, particularly after the age of 10 years. Participation rate disproportionately changes across various types of physical activity. Previous studies have indicated that adolescents are more inclined to participate in individualistic physical activities than team-based activities.

Sustenance in participation in different types of physical activities also depends on many factors, such as availability, opportunity, and cost. For instance, organized or structured activities require a coach, which increases the cost to participate or sustain in these activities for a prolonged period.

In contrast, unorganized or unstructured activities do not require an instructor or coach and increase the probability of long-term sustenance of these forms of physical activities. However, more factors drive sustainability and change in physical activity participation, which requires further research for proper understanding.

The majority of available studies are limited by short follow-up periods. In addition, these studies have examined a narrow set of physical activity types. To date, no studies have determined the main predictors of sustainability or change in physical activity participation.

However, it is imperative to identify the types of physical activities more likely to be continued or discontinued over a prolonged period. This information will help develop effective interventions to improve adolescent physical activity participation.

A previous study has pointed out that the onset of puberty predicts changes in physical activity participation during adolescence. Puberty is characterized by biological maturation. Puberty-timing is associated with many biological functions related to strength, weight, and height, and psychological changes.

Compared to boys, same-age girls are more inclined to drop out from participating in different physical activities after puberty. It has been observed that earlier-maturing girls are less active due to changes in body composition, lower self-esteem, and feelings of self-consciousness.

More research is required to understand the associations between puberty timing and physical activity discontinuation in the context of unorganized and individual physical activity participation. Age differences between individuals within the same group could be another predictor of physical activity participation.About the study

The current study focussed on investigating the gender-specific longitudinal involvement, uptake rates in various types and contexts of physical activity, and re-engagement rates among adolescents between the ages of 11 and 17 years. This study focussed on predicting gender-specific discontinuation of structured, unstructured, individual, and group-based physical activities based on relative and puberty timing.

The current study used data from the Monitoring Activities of Teenagers to Comprehend Their Habits (MATCH) study. MATCH is an ongoing longitudinal study focusing on comprehending physical activity behavior from childhood to early adulthood. Study findings

The current study evaluated grade 6 physical activity participation data, including the participation of 781 individuals, including 57% of girls and 43% of boys. On average, participants were 11.5 years of age at the study onset and 17.4 at the study end. The study cohort contained 57% of grade 6 participants who had on-time puberty, 14.2% showed early-maturing, and 29.3% were late-maturing.

A decrease in participation in most physical activities was observed from 11 to 17 years of age. Although most group-based and organized activities were not resumed after discontinuation, a higher re-engagement rate was observed for individual and unorganized activities.

Even though a higher rate of discontinuance was found in certain types of physical activities during adolescence, many participants also showed a greater inclination to continue participating in individual and unorganized physical activity by the end of high school.

No association between puberty timing and risk of dropping out of physical activities was found among boys. Birth quartile was a better predictor of physical activity dropout among boys than girls. Earlier-maturing girls were more inclined to discontinue organized activities than those with late or normal puberty time. Notably, boys born between April and June, i.e., second quartile (Q2), exhibited a lower risk of discontinuing organized, unorganized, individual, and group-based activities.

The finding of this study is consistent with previous studies conducted a decade ago exhibiting a similar declining pattern in physical activity participation among teenagers. This physical activity pattern during adolescence may be a natural aging process. Conclusions

The overall participation in most physical activities included in this study declined during adolescence. This study highlighted that individual activities were generally sustained longer than group-based activities. Furthermore, compared to organized activities, unorganized activities showed a better likelihood of prolonged sustenance.

Therefore, more facilities for access to individual and unorganized physical activity for adolescents must be provided. Home exercises, running/jogging, and weight training showed the highest potential for uptake, re-engagement, and maintenance during adolescence.

Journal reference:Gallant, F. et al. (2023) Puberty timing and relative age as predictors of physical activity discontinuation during adolescence. Scientific Reports, 13(1), pp.1-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40882-3

02

Moral Reasoning Creates Distinct Patterns of Activity in the Brain

Every day we encounter circumstances we consider wrong: a starving child, a corrupt politician, an unfaithful partner, a fraudulent scientist. These examples highlight several moral issues, including matters of care, fairness and betrayal. But does anything unite them all?

Philosophers, psychologists and neuroscientists have passionately argued whether moral judgments share something distinctive that separates them from non-moral matters. Moral monists claim that morality is unified by a common characteristic and that all moral issues involve concerns about harm. Pluralists, in contrast, argue that moral judgments are more diverse in nature.

Fascinated by this centuries-old debate, a team of researchers set out to probe the nature of morality using one of moral psychology’s most prolific theories. The group, led by UC Santa Barbara’s René Weber, intensively studied 64 individuals via surveys, interviews and brain imaging on the wrongness of various behaviors.

They discovered that a general network of brain regions was involved in judging moral violations, like cheating on a test, in contrast with mere social norm violations, such as drinking coffee with a spoon. What’s more, the network’s topography overlapped strikingly with the brain regions involved in theory of mind. However, distinct activity patterns emerged at finer resolution, suggesting that the brain processes different moral issues along different pathways, supporting a pluralist view of moral reasoning. The results, published in Nature Human Behaviour even reveal differences between how liberals and conservatives evaluate a given moral issue.

Subscribe to Technology Networks’ daily newsletter, delivering breaking science news straight to your inbox every day.Subscribe for FREE“In many ways, I think our findings clarify that monism and pluralism are not necessarily mutually exclusive approaches,” said first author Frederic Hopp who led the study as a doctoral student in UC Santa Barbara’s Media Neuroscience Lab. “We show that moral judgments of a wide range of different types of morally relevant behaviors are instantiated in shared brain regions.”

That said, a machine-learning algorithm could reliably identify which moral category, or “foundation,” a person was judging based on their brain activity. “This is only possible because moral foundations elicit distinct neural activations,” Hopp explained.

The group was guided by Moral Foundations Theory (MFT), a framework for explaining the origins and variation in human moral reasoning. “MFT predicts that humans possess a set of innate and universal moral foundations,” Weber explained. These are generally organized into six categories:Issues of care and harm,Concerns of fairness and cheating,Liberty versus oppression,Matters of loyalty and betrayal,Adherence to and subversion of authority,And sanctity versus degradation.

The framework arranges these foundations into two broad moral categories: care/harm and fairness/cheating emerge as “individualizing” foundations that primarily serve to protect the rights and freedoms of individuals. Meanwhile loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion and sanctity/degradation form “binding” foundations, which primarily operate at the group level.

The researchers created a model based on MFT to test whether the framework — and its nested categories — was reflected in neural activity. Sixty-four participants rated short descriptions of behaviors that violated a particular set of moral foundations, as well as behaviors that simply went against conventional social norms, which served as a control. An fMRI machine monitored activity across different regions of their brains as they reasoned through the vignettes.

Certain brain regions distinguished moral from non-moral judgment across the board, such as activity in the medial prefrontal cortex, temporoparietal junction and posterior cingulate, among other regions. Participants also took longer to rate moral transgressions than non-moral ones. The delay suggests that judging moral issues may involve a deeper evaluation of an individuals’ actions and how they relate to one’s own values, the authors said.

“Although moral judgments are intuitive at first, deeper judgment requires responses to the six ‘W questions,’” said senior author Weber, director and lead researcher of UCSB’s Media Neuroscience Lab, and a professor in the Departments of Communication and of Psychological and Brain Sciences. “Who does what, when, to whom, with what effect, and why. And this can be complex and takes time.” Indeed, moral reasoning recruited regions of the brain also associated with mentalizing and theory of mind.

The researchers also found that transgressions of loyalty, authority and sanctity prompted greater activity in regions of the brain associated with processing other people’s actions, as opposed to the self. “It was surprising to us how well the organization into ‘individualizing’ versus ‘binding’ moral foundations is reflected on the neurological level in multiple networks,” Weber said.

Next, the authors developed a decoding model that accurately predicted which specific moral foundation or social norm individuals were judging from fine-grained activity pattern across their brains. This would not have been possible if all moral categories were unified at the neurological level, they explained.

“This supports MFT’s prediction that each moral foundation is not encoded in a single ‘moral hotspot,’” the authors write, “but (is instead) instantiated via multiple brain regions distributed across the brain.” This finding suggests that the distinct moral categories proposed by Moral Foundations Theory have an underlying neurologic basis.

In this way, moral reasoning is similar to other mental tasks: it elicits characteristic patterns across the brain, with nuances based on the specifics. For instance, looking at pictures of houses and faces activates a brain region known as the ventral temporal cortex. “However, when looking at the pattern of activation in this region, one can clearly discern whether someone is looking at a house or a face,” Hopp explained. Analogously, moral reasoning activates certain regions of the brain, “yet, the activation patterns in those same regions are highly distinct for different classes of moral behaviors, suggesting that they are not unified.”

Far from merely an esoteric exercise, MFT provides a robust framework for understanding group identity and political polarization. Mounting evidence from survey and behavioral experiments suggests that liberals (progressives) are more sensitive to the categories of care/harm and fairness/cheating, which primarily protect the rights and freedoms of individuals. Conservatives, in contrast, place greater emphasis on the loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation categories, which generally operate at the group level.

“Indeed, our results provide evidence at the neurological level that liberals and conservatives have complex differential neural responses when judging moral foundations,” Weber explained. That means individuals at different points along the political spectrum likely emphasize completely different values when evaluating a particular issue.

This paper is part of an avenue of research that the Media Neuroscience Lab embarked on in 2016, aiming to understand how humans make moral judgments, and how the underlying processes vary across more and less realistic scenarios. “the observation that we can reliably decode which moral violation an individual is perceiving also opens exciting avenues for future research: Can we also decode if a moral violation is detected when reading a news story, listening to a radio show, or even when watching a political debate or movie?” Hopp said. “I think these are fascinating questions that will shape the next century of moral neuroscience.”

The study’s co-investigators include renowned neuroscientist and moral philosopher Walter Sinnott-Armstrong from Duke University and Scott Grafton, a professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. Jacob Fisher and Ori Amir also contributed as co-authors, and were, respectively, a Ph.D. student and a postdoctoral fellow in Weber’s Media Neuroscience Lab at the time the work was conducted.

Ultimately, the researchers say, our ability to cooperate in groups is guided by systems of moral and social norms, and the rewards and punishments that result from adhering to or violating them. “For millennia, fables and fairy tales, nursery rhymes, novels, and even ‘the daily news’ all weave a tapestry of what counts as good and acceptable or as bad and inacceptable,” Weber said. “Our results contribute to a better understanding of what moral judgments are, how they are processed, and how they can be predicted across different groups.”

Reference: Hopp FR, Amir O, Fisher JT, Grafton S, Sinnott-Armstrong W, Weber R. Moral foundations elicit shared and dissociable cortical activation modulated by political ideology. Nat Hum Behav. 2023:1-17. doi: 10.1038/s41562-023-01693-8

This article has been republished from the following materials. Note: material may have been edited for length and content. For further information, please contact the cited source.

03

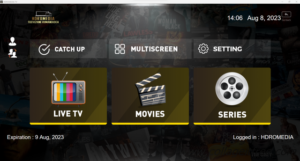

Public Health Activity changes leaders

1 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – FORT CAVAZOS, Texas – Lt. Col. Sheila Medina former U.S. Army Fort Hood Public Health Activity bids farewell during a change of command ceremony at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL

1 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – FORT CAVAZOS, Texas – Lt. Col. Sheila Medina former U.S. Army Fort Hood Public Health Activity bids farewell during a change of command ceremony at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL 2 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – – Lt. Col. Luke Lindaman receives the guidon Col. Stephanie Mont, commander, Public Health Command – Central, in a change of command ceremony for the U.S. Army Public Health Activity – Fort Hood (Fort Cavazos name change pending) at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, CRDAMC Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL

2 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – – Lt. Col. Luke Lindaman receives the guidon Col. Stephanie Mont, commander, Public Health Command – Central, in a change of command ceremony for the U.S. Army Public Health Activity – Fort Hood (Fort Cavazos name change pending) at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, CRDAMC Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL 3 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – FORT CAVAZOS, Texas – Col. Stephanie Mont, commander, Public Health Command, Central, addresses the audience during a change of command ceremony for U.S. Army Public Health Activity – Fort Hood (Fort Cavazos name change pending) at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL

3 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – FORT CAVAZOS, Texas – Col. Stephanie Mont, commander, Public Health Command, Central, addresses the audience during a change of command ceremony for U.S. Army Public Health Activity – Fort Hood (Fort Cavazos name change pending) at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL 4 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – – Lt. Col. Luke Lindaman, incoming commander, U.S. Army Public Health Activity addresses the audience during a change of command ceremony at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL

4 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – – Lt. Col. Luke Lindaman, incoming commander, U.S. Army Public Health Activity addresses the audience during a change of command ceremony at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL 5 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – FORT CAVAZOS, Texas – Lt. Col. Luke Lindaman, incoming commander, U.S. Army Public Health Activity stands before the audience with Col. Stephanie Mont, commander, commander, Public Health Command – Central, and former PHA commander Lt. Col. Sheila Medina during a change of command ceremony in which she took command from Medina at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL

5 / 5 Show Caption + Hide Caption – FORT CAVAZOS, Texas – Lt. Col. Luke Lindaman, incoming commander, U.S. Army Public Health Activity stands before the audience with Col. Stephanie Mont, commander, commander, Public Health Command – Central, and former PHA commander Lt. Col. Sheila Medina during a change of command ceremony in which she took command from Medina at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21. (U.S. Army Photo by Rodney Jackson, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Public Affairs) (Photo Credit: Rodney Jackson) VIEW ORIGINAL

FORT CAVAZOS, Texas – The U.S. Army Public Health Activity – Fort Hood (official name change to PHA-Fort Cavazos pending) welcomed incoming commander Lt. Col. Luke Lindaman and bid farewell to Lt. Col. Sheila Medina in a change of command at the III Corps headquarters Aug. 21.

In her comments to the audience presiding officer, Col. Stephanie Mont, commander, Public Health Command – Central gave them a little insight on just how important this public health activity is.

“This public health activity consists of over 200 personnel at 29 geographically separate installations responsible for providing service and support across eight States, on every single Army, Navy, Airforce, Space Force and Marine Corps installation, said Mont. “They do this in a resource challenged environments, on some of the military’s most austere locations within the continental United States. They ensure the readiness of government animals for their missions and the protect the health of service members and their families through veterinary preventative medicine and food protection measures every day.”

These Soldiers do this while also ensuring their readiness to deploy where needed globally she added.

A family nurse practitioner, Medina explained that prior to being the commander she wasn’t really aware of all that the public health activity did and thought that it couldn’t be any harder than working in the emergency room with providers and medics every day.

“I gained an appreciation really fast for what each of you did,” said Medina. “I tried to reflect and think back to why I never really heard about vet services, and I immediately came up with the answer, it’s because you are so amazing and good at your job.”

Animals are being cared for and nobody’s getting food poisoning and it’s all because of you, she added.

Medina will move on to become the chief of clinical operations U.S. Army Central.

Mont stated that Medina faced every challenge head on, embraced her people, fought for resources and made tough decisions, and thanked her and her family for being there for her and supporting her every day ensuring she was ready to take command.

“Team Medina is a wonderful Army family,” said Mont.

Lindaman arrives from Force Health Protection for Southern European Task Force – Africa where he was the Chief.

“As I take this charge and lead this organization into its next chapter, I have one promise to each and every one of you regardless of you position within the organization that I will continue to look,” said Lindaman. “I look forward to learning and obviously enjoying working with every single one of you.”

“When our nation needs forward deployed veterinary personnel, the Army veterinary service answers that call and provides that same high quality veterinary medical and veterinary public health and food safety support wherever needed,” said Mont.

Post Comment